Julius Hemphill is one of my all-time-great musical heroes, a member of a fairly short list that includes Carla Bley, Steve Lacy, Jimmy Giuffre, George Russell, John Zorn, Willem Breuker, and Frank Sinatra. (And then there’s Captain Beefheart, Anthony Braxton, Jack Bruce, Bernard Herrmann, Derek Bailey, Robert Wyatt, Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber, Henry Threadgill, Joe Harriott, Tim Buckley, Heiner Goebbels, The Residents, John Coltrane, Charles Ives, Frank Zappa, Raymond Scott… But I digress.)

Hemphill made a unique contribution to contemporary music, not only through his distinctive improvisational and compositional techniques, but also in terms of his innovative approaches to small-group instrumentation, recording studio experimentation, independent label creation, live performance production, and multi-disciplinary collaboration, encompassing poetry, dance, theatre, film, and the visual arts.

The strictures of neoconservatism were anathema to Hemphill – in a 1994 interview he described the involvement of Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Crouch in the Jazz at Lincoln Center program as “the death of creative music late in the 20th century”, and he observed: “Well, you often hear people nowadays talking about the tradition, tradition, tradition. But they have tunnel vision on this tradition. Because tradition in African-American music is as wide as all outdoors.”

Hemphill died in 1995, aged 57 (from complications related to diabetes), leaving behind a relatively small recorded legacy, spanning little more than 20 years, with only 15 albums released under his own name during his lifetime, plus his work with the World Saxophone Quartet and various guest/sideman gigs. But the range, depth, and richness of this music remain unparalleled in the history of twentieth-century (and twenty-first-century) music. And if that sounds a tad hyberbolic, trust me, it’s not: just listen.

The Playlist is in four parts, each organized chronologically, and with frequent annotations:

1) Hemphill’s own recordings, including the later chamber music and Saxophone Sextet records, in which I highlight one (or two) of my favourite tracks from each album (although I recommend listening to all of them)

2) A full list of Hemphill’s recorded compositions for the World Saxophone Quartet – an 11-year chronicle of his compositional gifts.

3) Hemphill’s appearances as a guest or sideman on other people’s records.

4) Recordings of Hemphill’s compositions by other people.

Click on any album cover to see it at 600 pixels, and to scroll through the galleries.

Note that all dates on the Playlist are recording dates, rather than release dates.

The Playlist is primarily on Spotify, and can be listened to as a stand-alone list, although that excludes a significant number of tracks that are only available on YouTube, Bandcamp, or Apple Music – the links for those tracks, along with links for all the individual Spotify tracks, are included in the listings below. Note that some recordings are not available online, but it’s worth the effort tracking them down on LP or CD. If you have any additions or corrections to make to the Playlist, please contact me by email.

I’ve been listening to Hemphill’s music since the mid-1970s and it never fails to delight, excite, challenge, and inspire me. This Playlist serves as both an introduction for newbies and a reminder for devotees of Julius’s extraordinary talents.

Alan Stanbridge, Toronto, 2024

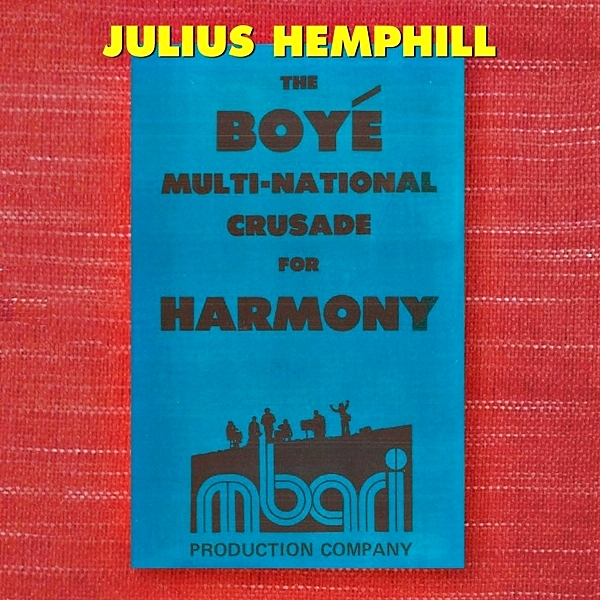

Before proceeding to the playlist proper, we have to pause to celebrate The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony, a fabulous 7CD box set on New World Records, and the most significant posthumous addition to Hemphill’s recorded output in many a year, expanding his discography under his own name by almost fifty percent.

Released in 2021, the set includes previously unreleased material recorded by Hemphill between 1977 and 1986, as well as performances of his chamber music from 2007. Curated by saxophonist, composer, and long-time Hemphill associate Marty Ehrlich, the collection draws on the Julius Hemphill Papers at the Fales Library of New York University, an archive which was created with the aid of the pianist Ursula Oppens, Hemphill’s partner during his later years. Kudos to New World Records for releasing this incredible set, and heartfelt thanks to Ehrlich for his tireless dedication over several years, organizing the archive and selecting the revelatory music that appears here, which features Hemphill in multiple contexts, from solo to quintet, plus spoken-word collaborations and music for piano and string quartet. It’s hard to pick individual highlights from this glorious cornucopia, but I was especially pleased to have more music from Julius’s duo with the amazing cellist Abdul Wadud, performing six previously unheard and unrecorded Hemphill compositions. And Ehrlich’s liner notes, along with his introductions and annotations to the compositions and archival material, and his contributions to the related website, represent invaluable additions to Hemphill scholarship, and to our understanding of this remarkable artist.

The full box set is available on Spotify – dip in anywhere/everywhere.

Or, better still, buy it from New World Records or on Bandcamp.

1) Hemphill’s Recordings Under His Own Name

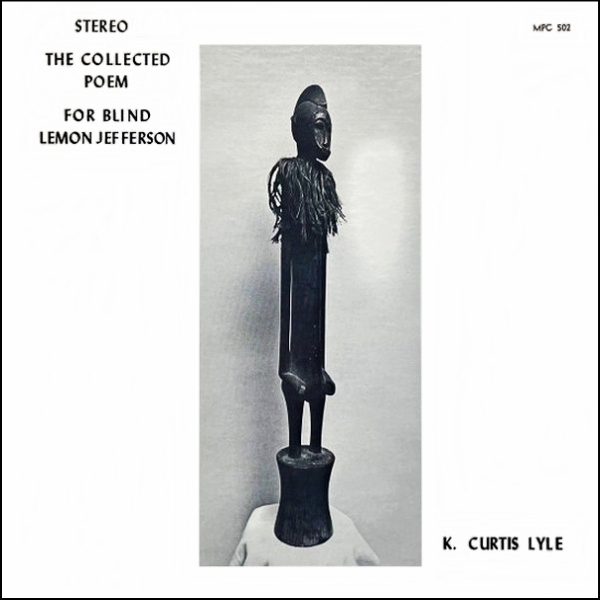

1971 – The Collected Poem for Blind Lemon Jefferson by K. Curtis Lyle (duo w. Lyle-Hemphill, plus Malinké Kenyatta on one track) (Mbari/Ikef) (YouTube)

Although credited solely to poet K. Curtis Lyle on the cover, this is effectively Hemphill’s first commercial recording, and it was the first release on his own Mbari record label. In this duo collaboration with Lyle, Hemphill improvises accompaniments on saxophone and flute, offering an early indication of his creative engagement with the spoken word. The album is currently available on YouTube, but I’ve also added Unfiltered Dreams: Wade in the Water (1982) to the Spotify playlist – a selection from a later Lyle-Hemphill performance documented on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony.

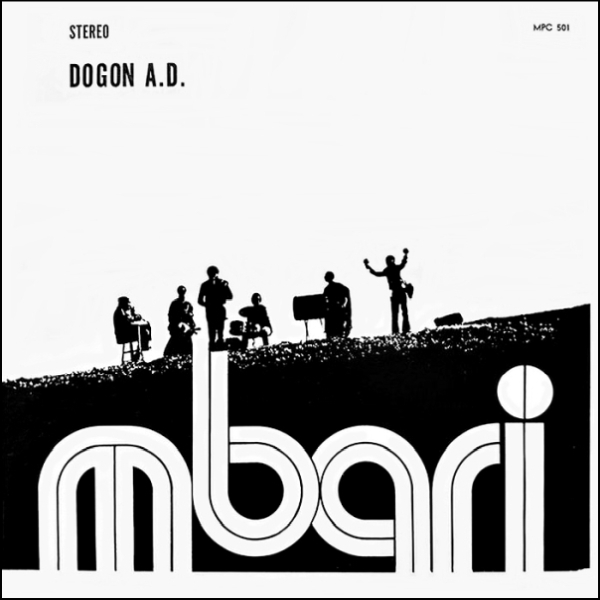

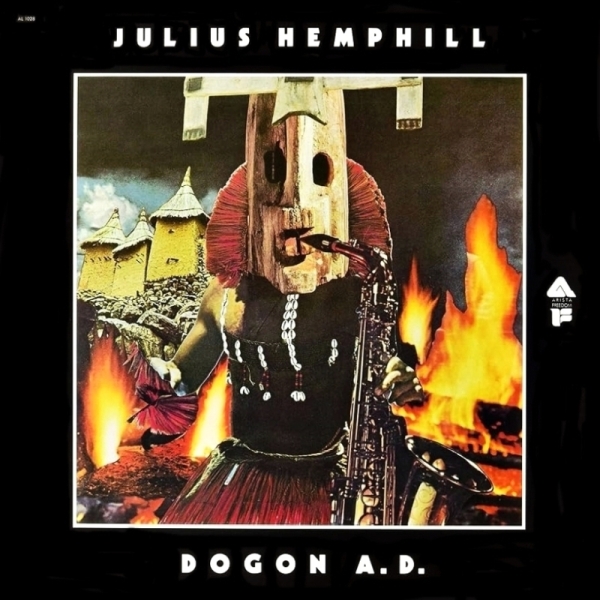

1972 – Dogon A.D., from Dogon A.D. (quartet w. Baikida Carroll-Abdul Wadud-Phillip Wilson) (Mbari/Arista-Freedom) (YouTube)

This is where it all began, with Julius announcing his singular voice on his own DIY record label, and later explaining, based on his research on the Dogon people of Mali and the fact that the Dogon only reveal part of their sacred dance ritual to tourists, that the “A.D.” in Dogon A.D. stands for “adaptive dance… I had in mind a dance all along.” In his Introduction to the Critical Editions of Hemphill’s compositions, Marty Ehrlich observes that in an archival video, apparently made before the album recording session, compositions from Dogon A.D. accompany a dance performance involving two dancers from the Katherine Dunham Company, with an ensemble featuring Carroll, Wilson, John Hicks playing vibes, and two Senegalese percussionists – another early example of Hemphill’s fascinating cross-disciplinary ambitions. On the album, the obsessive rhythm of the title track (which Ehrlich explains is in 11/16 with a 4/4/3 beat pattern) is magnificently sustained by Wadud and Wilson, and the piece features intense, burning solos by Hemphill and Carroll, sounding unlike any other music of the period. Or, in fact, any other music of any other period – the number of recorded versions of Dogon A.D. is a testament to its singularity.

The album was reissued by Arista-Freedom in 1977 with revised cover art, which was not sanctioned by Hemphill. It was reissued again in 2011 by International Phonograph with the same cover, but in a package that also included the original Mbari artwork. The CD was remastered (offering a significant improvement in sound quality) and expanded to include The Hard Blues, which had been recorded at the 1972 session but initially excluded for reasons of space on the original LP, and not issued until 1975 on ‘Coon Bid’ness. (The International Phonograph reissue is available on CD and vinyl, but does not appear to be available in digital format on any of the streaming platforms).

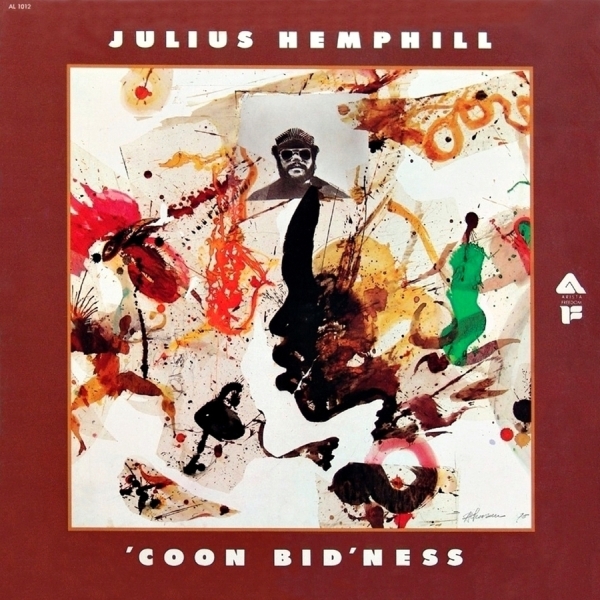

1972/1975 – The Hard Blues; Skin 1, from ‘Coon Bid’ness (The Hard Blues: quintet w. Baikida Carroll-Abdul Wadud-Phillip Wilson-Hamiet Bluiett; Skin 1: sextet w. Arthur Blythe-Hamiet Bluiett-Abdul Wadud-Barry Altschul-Daniel Ben Zebulon) (Arista-Freedom)

This album was my earliest encounter with Hemphill’s music, and I can still remember the visceral thrill of hearing The Hard Blues for the first time. In a published essay in 2010, I characterized Hemphill’s remarkable alto solo on this piece as “one of the finest saxophone statements ever committed to disc, bringing new pleasures on repeated listenings over a period of more than 30 years.” Almost 15 years later, I see little reason to revise that opinion.

Skin 1 is from the 1975 session, one of four tracks that effectively formed an extended suite on the first side of the original LP.

Hemphill’s deliberately provocative album title references the problematic history of minstrelsy but simultaneously reclaims that history, celebrating the enduring strength of African American culture in the face of systemic white racism. The overall album concept, incorporating cover art by Bill Hoffman and poems by Hemphill and Wilma Moses on the back cover, was also part of Hemphill’s wry commentary on the United States in its Bicentennial year, as he made clear in a 1994 interview: “I was just getting in some bicentennial licks.”

Interestingly, however, having happily resorted to awkward African stereotypes for the new cover of Dogon A.D. in 1977, the executives at Arista-Freedom were in rather more timid mood when it came to reissuing their own ‘Coon Bid’ness on CD in 1995, which was clumsily repackaged under the less in-your-face title Reflections (which at least had the distinction of being the name of a piece on the album), accompanied by lazily mimetic ad agency cover art (“Reflections, get it?”). To add injury to insult, the CD itself was an extremely poor digital transfer, with multiple drop-outs and sonic imperfections throughout The Hard Blues, the album’s 20-minute tour de force. Hemphill had expressed reservations about his record deal with Arista as early as 1978, in an interview with Coda magazine, characterizing it as “mostly a matter of expediency” and describing the avant-garde series of which his music was a part as “quite haphazard”, and he certainly deserved much better than this shoddy reissue, especially after his passing.

1976 – Pensive, from Wildflowers 4: The New York Loft Jazz Sessions (quintet w. Hemphill-Abdul Wadud-Bern Nix-Phillip Wilson-Don Moye) (Douglas/Knitting Factory) (YouTube)

An interesting lineup for this quintet, with Nix’s presence marking the early appearance of the electric guitar in one of Hemphill’s groups. The piece was recorded during two weeks in May at Studio Rivbea, Sam Rivers’s loft space, and issued as part of an outstanding 5-LP series featuring the cream of the New York creative music scene. The five volumes were reissued as a 3CD set (currently unavailable on Spotify in Canada, but search for it wherever you are).

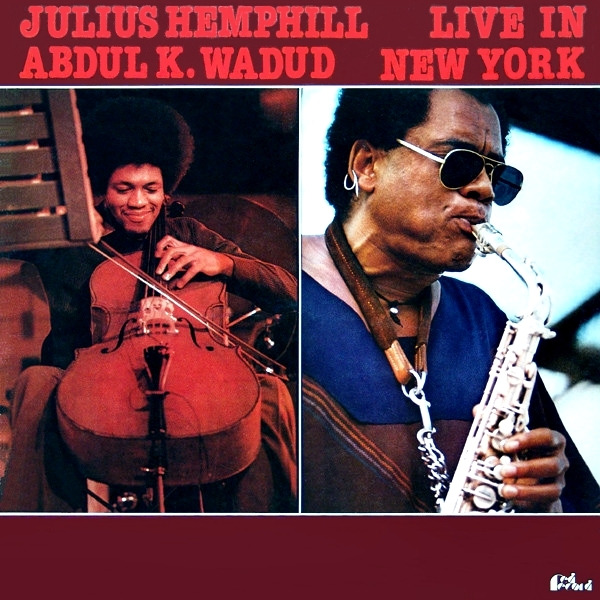

1976 – Echo 1 (Morning), from Live in New York (duo w. Abdul Wadud) (Red Records) (The CD reissue has a revised cover)

Wadud was Hemphill’s most important early collaborator, celebrated for his “extraordinary gifts” by Julius in his liner notes. Hemphill observes that much of this music is improvised, although both players bring a composerly sense of form and structure to this incredible duo performance. The sombre theme Pensive, recorded at the Wildflowers series a week or so earlier, is heard again on this album.

1977 – Hotend; Kansas City Line, from Blue Boyé (solo with overdubbing) (Mbari/Screwgun) (Bandcamp; YouTube – go to 42:55)

On this first solo album, employing alto saxophone, soprano saxophone, and flute (as well as occasional “hambone” percussion), Hemphill makes extensive use of overdubbing, a process that allowed him to realize the multi-voiced ideas that he presents here, and which he would pursue further in Roi Boyé & The Gotham Minstrels. By the late 1970s, recording studio practices such as overdubbing and multitracking were considerably less controversial than they had been in earlier decades (see Chapter 5 of my book, Rhythm Changes, for a brief historical overview), and Hemphill’s approach on this album represents an enormously creative vindication of techniques that were previously and routinely denounced as studio “trickery.”

The album includes five tracks featuring Hemphill in often tightly-wound overdubbed conversations with himself in trio and duo settings, along with two flute solos (illustrating his singular approach to the instrument), plus Kansas City Line, a ten-bar blues that receives an astonishing performance on solo alto saxophone, reflecting, as Marty Ehrlich suggests, how Hemphill “heard and extended the bebop vernacular developed by Charlie Parker.”

Initially released on Hemphill’s Mbari label, with Tim Berne serving as Assistant Producer, the album was reissued by Berne in 1998 on his own Screwgun label, in an elaborate accordion package with a new cover design by Stephen Byram, incorporating elements of the original artwork by Oliver Lee Jackson. In his liner notes (and in a 2009 interview), Tim relates the tale of the recording session, which took place during a freezing cold January in a freezing cold and somewhat modest basement studio in Larchmont, New York, with Julius in his overcoat throughout. The knowledge that Hemphill completed the entire album, including overdubs, in “a few hours”, and under these conditions, simply confirms the sharply focused nature of his unique musical vision, which is on full display on this remarkable record.

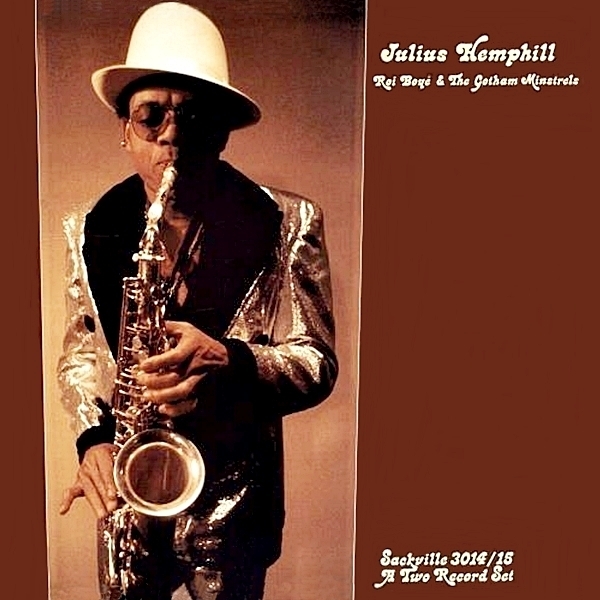

1977 – Part 2 (“42nd Street. Watch the closing doors.”), from Roi Boyé & The Gotham Minstrels (solo with overdubbing plus tape) (Sackville) (The CD reissue has a revised cover)

Recorded in Toronto in March 1977, a few weeks after Blue Boyé, this album is a close cousin to the earlier record, employing many of the same studio techniques, although adopting a somewhat different artistic approach. Characterized by Hemphill as an “audiodrama,” Roi Boyé expands upon the often latent theatrical elements in Blue Boyé (which were manifested most obviously in the flute solos), with Julius resplendent on the cover in a gold lamé tuxedo and cream derby, in character as his alter-ego, Roi Boyé, reflecting his interest in “the rich and varied traditions of costuming as they are reflected in the archives of American show business.”

Filling two LPs in its original release, this extended piece is a fascinating collage of overdubbed alto, soprano, flute, and spoken word (using Hemphill’s own texts) plus prerecorded tape elements of environmental sounds from New York City (and, at the very end, what sounds like excerpts from a speeded-up cartoon). In his informative liner notes, Hemphill observes the centrality of “orchestrated language that proceeds from the rhythmic impulses of the spoken word,” anticipating by several years similarly inspired work by Scott Johnson and René Lussier, and, perhaps envisioning criticisms of the type highlighted in my comments above on Blue Boyé, he argues, carefully and insightfully, that the “use of prepared tapes in no way hampers the fluidity and creativity of the performer.”

Some observers have suggested that the overdubbed aspect of these two solo albums represents a precursor of Hemphill’s subsequent work for multiple reed instruments, whether with the World Saxophone Quartet or his own Sextet, although they are better understood as belonging to a distinct, parallel aspect of Hemphill’s artistic practice, in which the use of overdubbing is not merely a matter of economic expediency (i.e. creating the impression of larger groups through studio means) but a specific creative choice, drawing on his multi-disciplinary interests and based on his stated need “to construct an alternative performance vehicle for the solo performer.” The often conversational nature of the overdubbed elements, coupled with the inherent theatricality of these “audiodramas,” sets these works apart from Hemphill’s extensive catalog of compositions for saxophone choir in which, rather than a focus on fashioning multi-voiced, studio-based options for himself as a soloist, the emphasis is on meticulous arrangement, harmonic movement, and performer interaction.

Finally, major kudos to Bill Smith – saxophonist, author, former editor of Coda magazine, and co-founder, with John Norris, of Sackville Records – for recording this ground-breaking and challenging work, as part of a historically significant series documenting primarily the African American jazz avant-garde of the 1970s and ’80s, including albums by Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Oliver Lake, Joseph Bowie, Wadada Leo Smith, Don Pullen, George Lewis, Anthony Davis, Joe McPhee, Archie Shepp, Barry Altschul, Karl Berger, and Dave Holland.

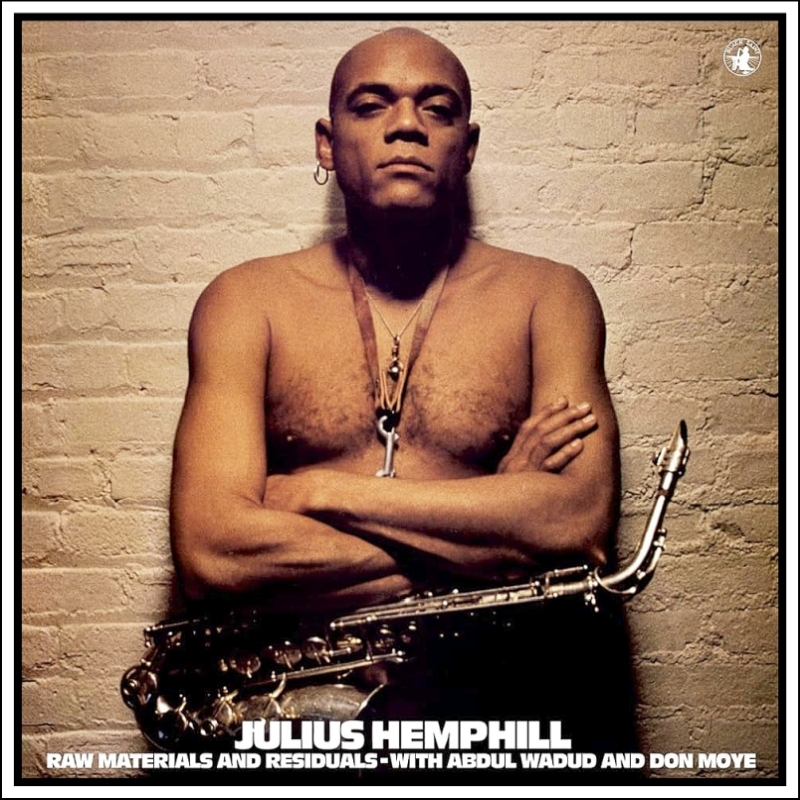

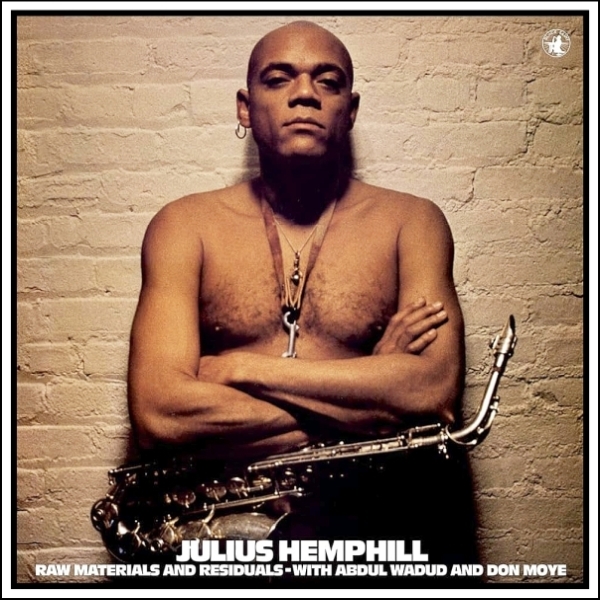

1977 – G Song, from Raw Materials and Residuals (trio w. Abdul Wadud-Don Moye) (Black Saint)

An exceptional trio, with Hemphill in the company of two long-standing collaborators. Wadud, in particular, is astonishing throughout, continuing his brilliant articulation of a new language for cello at the nexus of composition and improvisation. The final piece, G Song, is one of Hemphill’s ostensibly simple groove tunes, which also encompasses a complex and riveting collective improvisation.

The cover photograph features Hemphill in one of his best “Fuck You” poses – head shaved, eyes fixed, chest bare, arms folded, alto akimbo, a single hoop earring highlighted against a painted brick wall – an image which I read as a further example (somewhat paradoxically, perhaps, given the bare chest part) of his already stated interest in “costuming” and theatricality, with Julius here playing another, different character drawn from the history of black entertainers and black bodies (Jack Johnson springs readily to mind). The contrasting photograph on the back cover of the LP – an ordinary guy in an overcoat blowin’ his horn in Brooklyn Bridge Park (Pier 2, to be exact) – offers yet another vision of our shape-shifting protagonist, accompanied by a liner note which, denying the apparently confrontational mood of the cover, is positively sweet in its aspirations: “it is our sincere desire that you, the audience, derive some genuine pleasure from our efforts.”

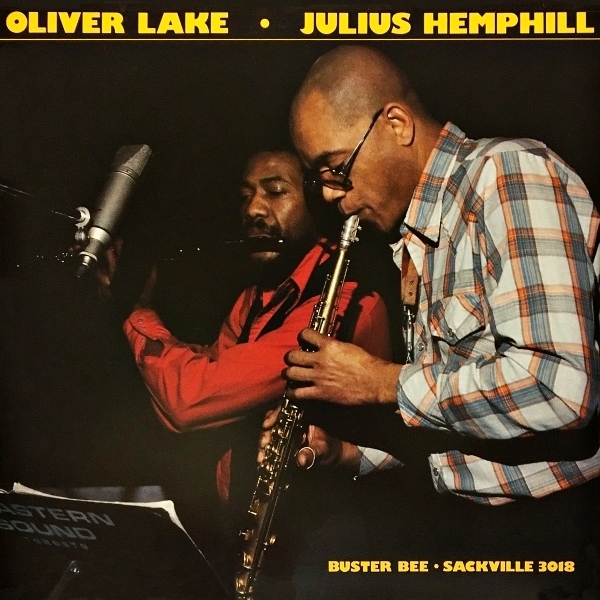

1978 – Buster Bee; Fertility; S, from Buster Bee (duo w. Oliver Lake) (Sackville) (The CD reissue has a revised cover)

More big thanks to Bill Smith for recording this lively duo session (exactly a year after Roi Boyé) during a visit to Toronto by the World Saxophone Quartet. Compositional credits are shared equally between the two players, with only one of the three Hemphill pieces featured here having a life beyond this session – S was retitled Lady S and arranged for quartet and big band, although sadly no commercial recordings are available.

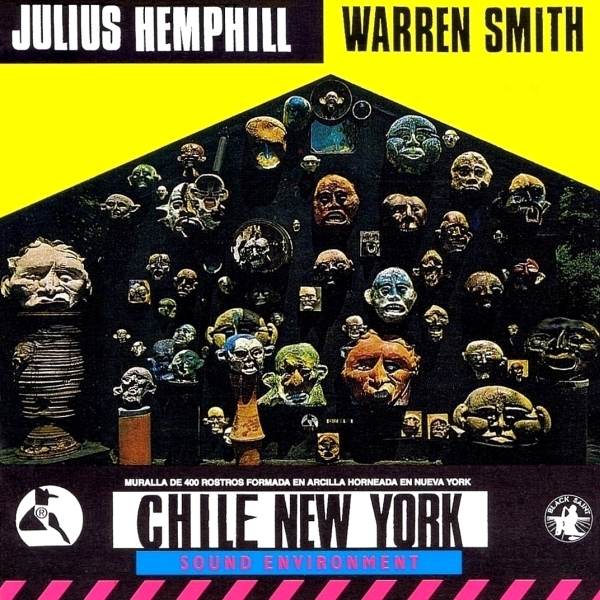

1980 – Seven, from Chile New York – Sound Environment (duo w. Warren Smith) (Black Saint)

A series of duet improvisations designed to accompany part of Wall of 400 Faces, a sculpture installation first presented at the City University of New York in May 1980 by artist and sculptor Jeff Schlanger, created in response to the Chilean coup of 1973. Hemphill and Smith interact productively throughout, although, as perhaps befits a “Sound Environment,” their improvisations can be somewhat meandering at times.

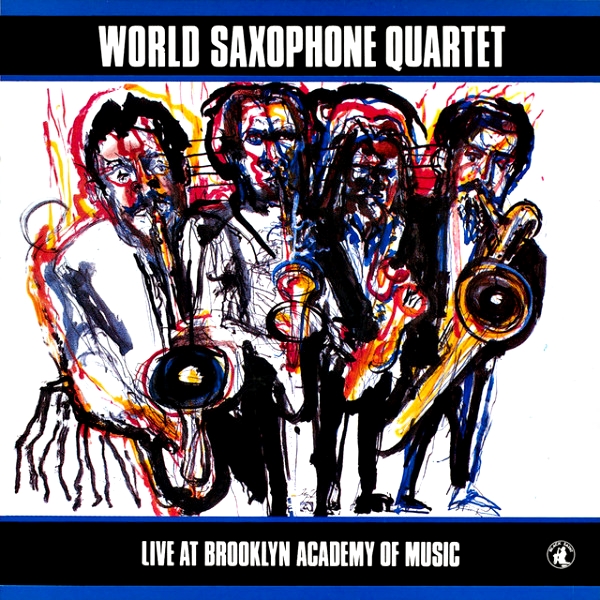

Schlanger, who goes by the moniker musicWitness®, is best known for his “live” paintings, created during music performances and festivals. His artwork has been experienced and exhibited widely, and appears on the covers of many albums of jazz and improvised music, including those by William Parker, Charles Gayle, and Billy Bang, as well as three others on this page: Fat Man and The Hard Blues, Live from the New Music Cafe, and the World Saxophone Quartet’s Live at Brooklyn Academy of Music.

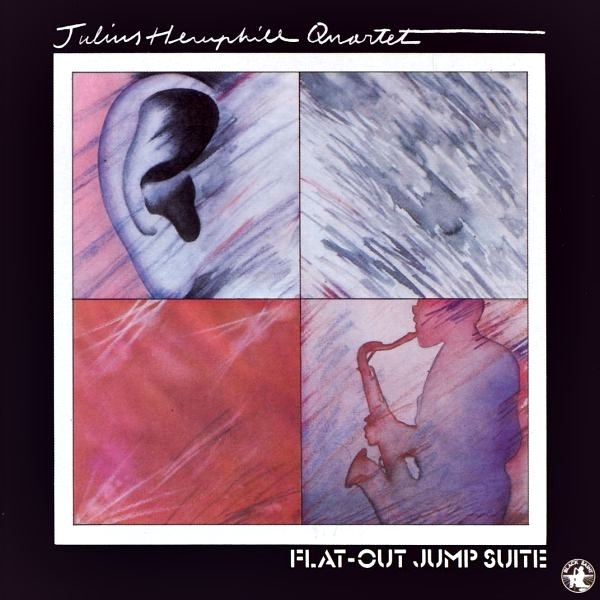

1980 – Body, from Flat-Out Jump Suite (quartet w. Olu Dara-Abdul Wadud-Warren Smith) (Black Saint)

Julius on Tenor (and Flute), back in the quartet context of Dogon A.D., with Dara and Smith replacing Carroll and Wilson on trumpet and drums. With the exception of Hemphill’s funky composition Body, the pieces on this album are collective improvisations, although Heart has a brief head arrangement, and Mind (2nd part) is a drum solo by Smith. (See/hear also the splendid versions of Body by the groups Do Tell and Broken Shadows, listed below.)

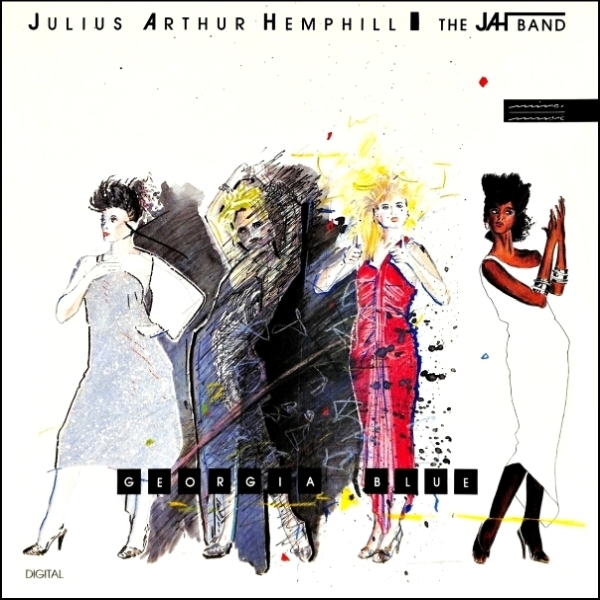

1984 – Dogon II, from Georgia Blue (The JAH Band – quintet w. Nels Cline-Steuart Liebig-Alex Cline-Jumma Santos) (Minor Music)

Sadly, this critically undervalued album (admittedly, it’s hard to ignore the generic 1980s cover art…) is not available online, but I’ve added the JAH Band track, One/Waltz/Time (1986), from The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony, to the Spotify playlist. Although the lineup is slightly different, with Santos out and Allan Jaffe added as a second guitarist alongside Nels Cline, the piece serves as a representative example of this distinctive band, illustrating Hemphill’s intriguing relationship with the electric guitar.

1987 – Solo II; Duo I, from Live at Kassiopeia (solo + duo w. Peter Kowald) (No Business) (Bandcamp)

Released in 2011, this album is a significant addition to Hemphill’s solo recorded work (live and unadorned) and offers further examples of his fertile, productive duo with Kowald, which had been hinted at only briefly on Kowald’s Duos: America (1990). Marty Ehrlich notes that the piece listed as Solo II is a version of Hemphill’s composition Kansas City Line, which was initially recorded on Blue Boyé.

1988 – C/Saw, from Julius Hemphill Big Band (w. Marty Ehrlich-John Purcell-John Stubblefield-J. D. Parran-David Hines-Rasul Siddik-Vincent Chancey-Frank Lacy-David Taylor-Bill Frisell-Jack Wilkins-Jerome Harris-Ronnie Burrage-Gordon Gottlieb) (Elektra/Musician)

In the context of a musical career in which he focused primarily on small groups, this album is a rare and much-valued recorded opportunity to hear Hemphill working with larger forces – and the results don’t disappoint, with inventive arrangements of his compositions, both new and old, and some inspired soloists.

1991 – Otis’ Groove; Floppy, from Fat Man and The Hard Blues (sextet w. Hemphill-Marty Ehrlich-James Carter-Carl Grubbs-Andrew White-Sam Furnace) (Black Saint)

This was Hemphill’s first recording after leaving the World Saxophone Quartet in 1989, and it represents a fascinating extension of that work, adding further voices to Julius’s compositional palette on this glorious series of 14 miniatures (none longer than seven minutes and one as short as two minutes). But don’t let brevity fool you – this is Hemphill in distilled form, close to his creative peak. This is also the only Sextet album to feature Julius as a playing member, before he had to withdraw for health reasons. With the exception of The Hard Blues, which first appeared on ‘Coon Bid’ness, all the pieces are first recordings, and although Otis’ Groove and Floppy are indicative of the funkier compositions here, choosing only one or two tracks from this amazingly rich album is a foolish undertaking – they’re all killer-dillers, and deserve your undivided attention.

1991 – Dogon A.D.; Georgia Blue, from Live from the New Music Cafe (trio w. Abdul Wadud-Joe Bonadio) (Music & Arts)

In his liner notes, Hemphill suggests that this is only his third recording with Wadud, which is accurate if we count only duo and trio settings (Live in New York, Raw Materials and Residuals) although the inclusion of Dogon A.D., ‘Coon Bid’ness, and Flat-Out Jump Suite makes this their sixth recording together. Numbers aside, any album featuring Hemphill and Wadud is to be treasured – there are far too few of them – and this live trio session offers an eclectic selection of new pieces and staples, for which Hemphill offers an interesting rationale: “I approach the use of my materials in the way others perform standard Tin Pan Alley type material. That is, I restrict my repertoire to my own compositions, and in the way that others reinterpret music by various composers, I reinterpret my own.” The stripped-down version of Dogon A.D. is especially pleasing – even though the initial recording of this piece was with a quartet, Julius had the remarkable ability, shared with Mingus, to make a small group sound like a band twice the size, and the trio version, lacking the additional horn, sounds positively skeletal in comparison. And the elegant, thoughtful reading of Georgia Blue, with typically sensitive accompaniment and soloing by Wadud, features Hemphill at his most exquisite, with the opening passages, for this listener, conjuring up distant echoes of Ornette’s equally beautiful Faithful, from The Empty Foxhole.

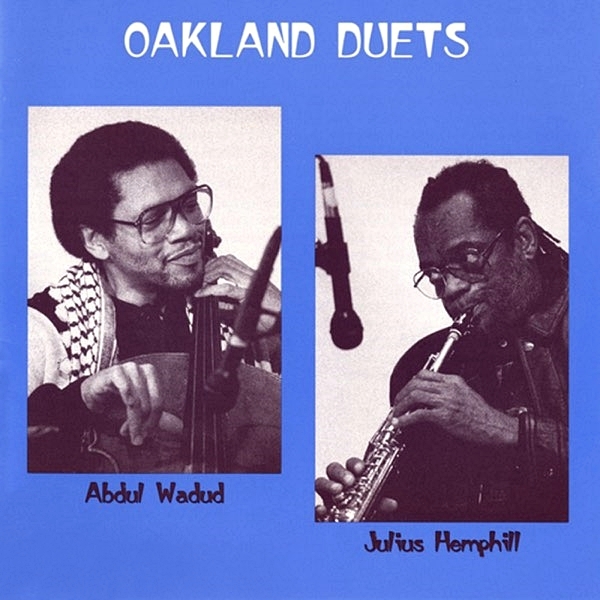

1992 – Me & Wadud, Part I, from Oakland Duets (duo w. Abdul Wadud) (Music & Arts)

This was Hemphill and Wadud’s last recording together, and the repertoire consists of three compositions by Hemphill (including the familiar C and For Billie, which had been recorded four years earlier on the Big Band record), one by Wadud, and two freely improvised pieces. Once again, in common with the notes to the earlier duet recording, Julius is warmly generous in his praise of his musical partner: “The beauty of the duet is the ease of communication… We’re so close musically that I feel like I have total freedom. In feel like I could play anything and he would respond. He knows he could do the same.”

1994 – Spiritual Chairs, from Five Chord Stud (sextet w. Tim Berne-Marty Ehrlich-James Carter-Sam Furnace-Andrew White-Fred Ho) (Black Saint)

Following heart surgery in 1993, Hemphill’s doctors advised him to stop playing the saxophone, and this recording sees Tim Berne joining the sextet, and Fred Ho replacing Carl Grubbs, with Julius conducting the ensemble. The album combines several new and existing pieces (including Mirrors and Georgia Blue) with compositions drawn from unrecorded stage performances, including Band Theme from Long Tongues: A Saxophone Opera and Spiritual Chairs, a gorgeous gospel-inspired piece, originally written for the dance piece, Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land, by the choreographer and dancer Bill T. Jones.

1997 – Void; What I Know Now, from At Dr. King’s Table (sextet w. Marty Ehrlich-Sam Furnace-Andy Laster-Gene Ghee-Andrew White-Alex Harding) (New World)

This was the first posthumous Sextet recording, with Ehrlich serving as Musical Director, and drawing on a remarkable selection of previously unrecorded (and in some cases previously unperformed) Hemphill compositions, including pieces from the aformentioned Last Supper and from Wind Rhythms, a suite originally written for the World Saxophone Quartet. The lively Void is a splendid and formerly unheard composition from the Hemphill archives, while What I Know Now, from a big band performance in 1981, is a deeply affecting piece with a lovely, understated alto solo by Ehrlich.

2003 – Water Music for Woodwinds – IV. Backwater, from One Atmosphere (w. Marty Ehrlich-Oliver Lake-Sam Furnace-Tim Berne-Aaron Stewart-Robert DeBellis-J.D. Parran) (Tzadik)

An extraordinary composition for seven woodwinds, premiered in 1976, and offering a significant prototype for Hemphill’s subsequent work for saxophone quartet and sextet, representing an early high point in his writing for woodwind choir. The piece is from a fascinating collection of Hemphill’s chamber music, including works for a trio of flute, cello and percussion, and for piano with string quartet. Thanks to Executive Producer John Zorn for the rare documentation of this material.

2003 – Fat Man, from The Hard Blues: Live in Lisbon (sextet w. Marty Ehrlich-Sam Furnace-Aaron Stewart-Alex Harding-Andy Laster-Andrew White) (Clean Feed)

The last Sextet recording (to date), recorded live at the Jazz em Agosto Festival, is a glorious, rip-roaring celebration of Hemphill’s music, played with joyous verve and energy. Ehrlich’s selection of compositions ranges widely over Hemphill’s career, drawing material from the three previous Sextet recordings and from the World Saxophone Quartet’s repertoire. Julius had been gone for over eight years by the time of this recording, but his music still sounds fresh and alive. The album is dedicated to Sam Furnace, who died six months after the concert recording.

2) Hemphill’s Recorded Compositions for the World Saxophone Quartet (Hemphill/Oliver Lake/David Murray/Hamiet Bluiett)

On the nine World Saxophone Quartet albums on which he appears, Hemphill is by far the most prolific composer of the four members, authoring 24 of the 49 original compositions included on these records (followed by Bluiett with nine and Lake and Murray with eight each). Several of these Hemphill compositions have appeared in different contexts, as indicated in the listings below, making for interesting comparisons across various instrumental groupings and time periods.

1977 – Dar El Sudan; Point of No Return, from Point of No Return (Moers) (The CD reissue has a revised cover) (YouTube – go to 0:00; 12:55)

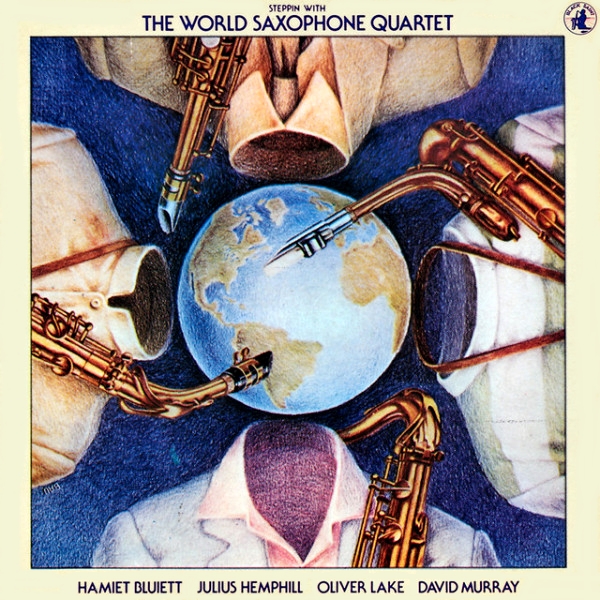

1978 – Steppin’; Dream Scheme; Hearts; R & B, from Steppin’ with the World Saxophone Quartet (Black Saint)

1980 – Plain Song; Connections; Pillars Latino, from W.S.Q. (Black Saint)

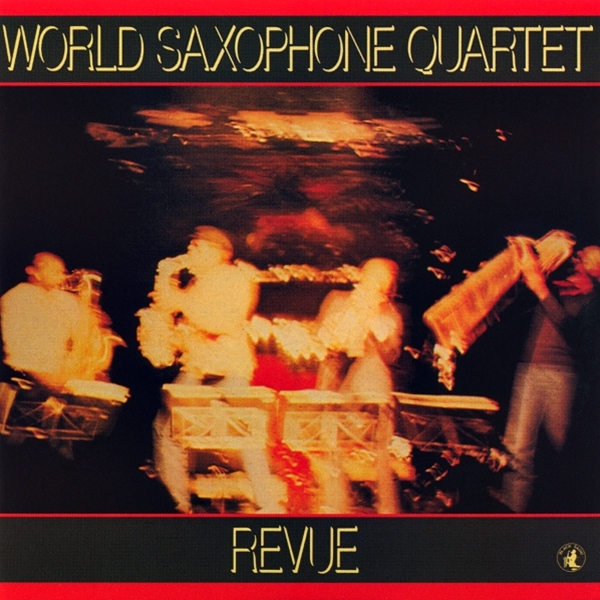

1980 – Revue; Affairs of the Heart; Slide; Little Samba, from Revue (Black Saint)

Rearranged for saxophone sextet, Revue also appears on The Hard Blues: Live in Lisbon (2003).

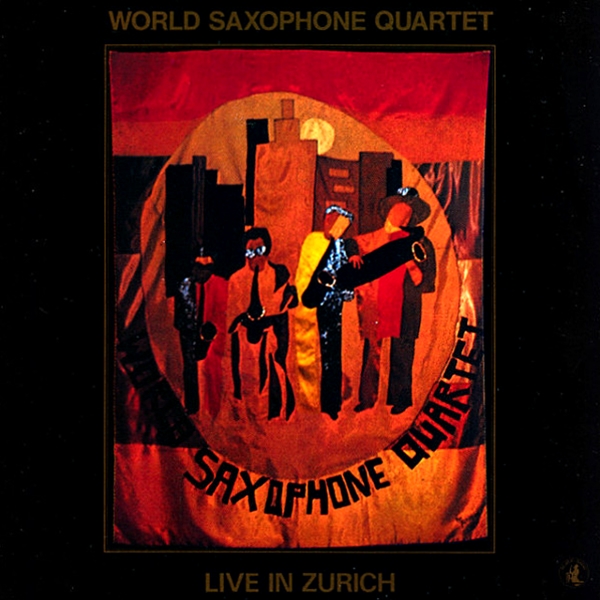

1981 – Funny Paper; Touchic; My First Winter; Bordertown; Steppin’; Stick, from Live in Zurich (Black Saint)

Rearranged for saxophone sextet, Touchic also appears on The Hard Blues: Live in Lisbon (2003).

Versions of Bordertown appear on both Julius Hemphill Big Band (1988) and Live from the New Music Cafe (1991).

1985 – One/Waltz/Time; Open Air (For Tommy); Georgia Blue, from Live at Brooklyn Academy of Music (Black Saint)

In a version for the JAH Band, One/Waltz/Time (1986) appears on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony.

One of the more ubiquitous of Hemphill’s pieces, Georgia Blue appears on the JAH Band album Georgia Blue (1984), the trio record Live from the New Music Cafe (1991), and, in an arrangement for saxophone sextet, on Five Chord Stud (1994) and The Hard Blues: Live in Lisbon (2003).

1986 – Take the ‘A’ Train (intro); Lush Life; Take the ‘A’ Train, from Plays Duke Ellington (Nonesuch)

No Hemphill compositions on this album, but the repertoire includes Julius’s gorgeous arrangements of two Billy Strayhorn classics. Marty Ehrlich characterizes these arrangements, and the two on Rhythm and Blues, as some of Hemphill’s “greatest creative works.”

1987 – Sweet D; Cool Red, from Dances and Ballads (Nonesuch)

Sadly, this fine album does not appear to be available online, despite the big name label.

1988 – Loopology, from Rhythm and Blues (Elektra-Musician)

In addition to this final composition for the World Saxophone Quartet, Hemphill contributes striking arrangements for Marvin Gaye and Ed Townsend’s Let’s Get It On (1973) and Mel London’s Messin’ With the Kid, first recorded by blues singer Junior Wells in 1960.

3) Hemphill’s Appearances as a Guest or Sideman on Other People’s Records

By my count, Hemphill made 12 appearances as a guest on record, most often as a featured soloist contributing to only part of an album, and usually playing other people’s music and arrangements. Exceptions include his compositional and arranging contributions to Lester Bowie’s Fast Last!, his performance of his own The Hard Blues on Flux by the JCAO, and the improvised contributions to Juma Sultan’s Father of Origin and Peter Kowald’s Duets: America. Hemphill also made eight appearances on record as a sideman, which I’m counting as album-length contributions as a group member, playing other people’s music and arrangements. There are two obvious exceptions to this rule: on Hustlers Convention, the band in which Hemphill plays as a sideman appears on only five tracks; and on Bill Cole’s Music for Yoruba Proverbs, as well as playing in the band Hemphill provided the arrangements for Cole’s compositions. Glad we got that sorted out.

c. 1970 – Untitled, Parts I and II (collective improvisations), from Father of Origin by Juma Sultan’s Aboriginal Music Society (octet w. Sultan-Ali Abuwi-Gene Dinwiddie-Rod Hicks-Phillip Wilson + “St. Louis guests”: Hemphill, Abdul Wadud, and Charles ‘Bobo’ Shaw) (Eremite)

An intriguing meeting of Sultan’s Woodstock, New York-based AMS and members of the Black Artists Group (BAG) from St. Louis, with drummer Wilson overlapping both categories. The exact date of this early 1970s performance is not known, but the consensus is that it happened at Woodstock’s Tinker Street Cinema. Released in 2011, this 2LP/CD set is out of print, and does not appear to be available online.

1973 – Spoon, from Hustlers Convention by Lightnin’ Rod (a.k.a. Jalal Mansur Nuriddin) (Includes five tracks on which Nuriddin is backed by Full Moon, a septet with Hemphill, Brother Gene Dinwiddie, Neil Larsen, Buzz Feiten, Fred Backmeier, Rocky Dejon, and Phillip Wilson) (United Artists/Douglas/Celluloid) (Also available on Bandcamp)

A pleasing historical curiosity, conceived and performed by Nuriddin, a founding member of The Last Poets and the self-styled “Grandfather of Rap“. Playing alongside Butterfield Blues Band mainstays Dinwiddie, Feiten, and Wilson, Hemphill’s contributions are submerged in the overall group sound, although it’s cool to know that Julius participated in what The Guardian has called “rap’s great lost album”.

(The tiresome grammar nerd in me had drafted a lengthy note on my concerns regarding the absence of an appropriately placed apostrophe in the title of this album, and my dismay at the multiple inconsistencies in styling to be found online and elsewhere, including the dubious usage on the original LP label, but I’ll let it pass.)

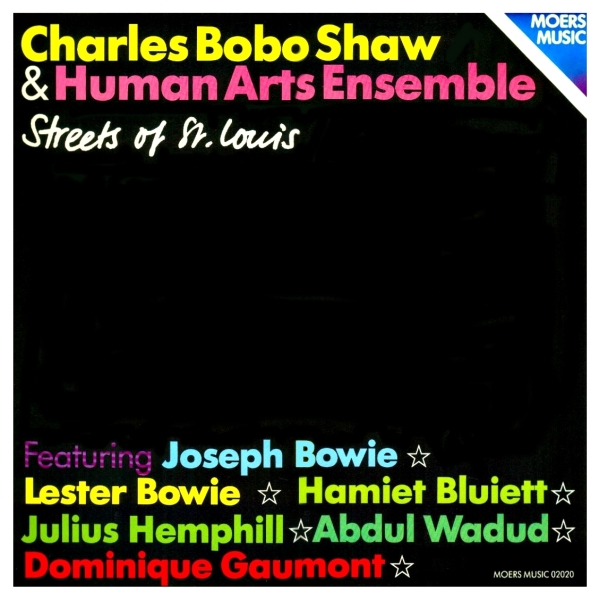

1974 – Hard Light, from Streets of St. Louis by Charles ‘Bobo’ Shaw and the Human Arts Ensemble (septet w. Shaw-Hemphill-Lester Bowie-Hamiet Bluiett-Joseph Bowie-Abdul Wadud-Dominique Gaumont) (Moers) (YouTube – go to 34:50)

Although I don’t quite share Dr. Chadbourne‘s utter disdain for this album, this was a sideman gig for Hemphill as part of Shaw’s impressive if undoubtedly rather wayward septet. But Julius’s solo contributions have a way of focusing the mind.

1974 – Banana Whistle (Hemphill); Fast Last/C (Bowie/Hemphill), from Fast Last! by Lester Bowie (Banana Whistle: octet w. Bowie-Hemphill-John Stubblefield-Joseph Bowie-Bob Stewart-John Hicks-Cecil McBee-Phillip Wilson; Fast Last/C: quintet w. Bowie-Hemphill-Hicks-McBee-Wilson) (Muse/32 Jazz) (YouTube – go to 5:13; 19:55)

Fantastic stuff! A joyous one-off collaboration capturing Bowie and Hemphill in rowdy, funky, irrepressible mood on compositions by both leader and guest. And don’t miss Hemphill’s stunning octet arrangement of Ornette’s Lonely Woman which opens the album, and the brief quintet statement of his composition C which concludes Bowie’s title track.

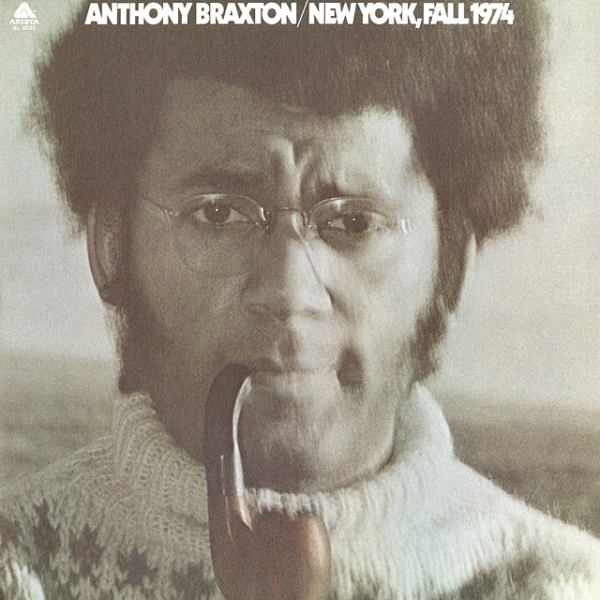

1974 – Composition 23A, from New York, Fall 1974 by Anthony Braxton (Arista-Freedom)

Hemphill performs as part of a saxophone quartet that includes Braxton, Oliver Lake, and Hamiet Bluiett, in what can be regarded, notwithstanding Braxton’s typically Braxtonian composition, as an intriguing precursor of the World Saxophone Quartet, formed in 1977 with David Murray filling the chair occupied by the composer on this recording.

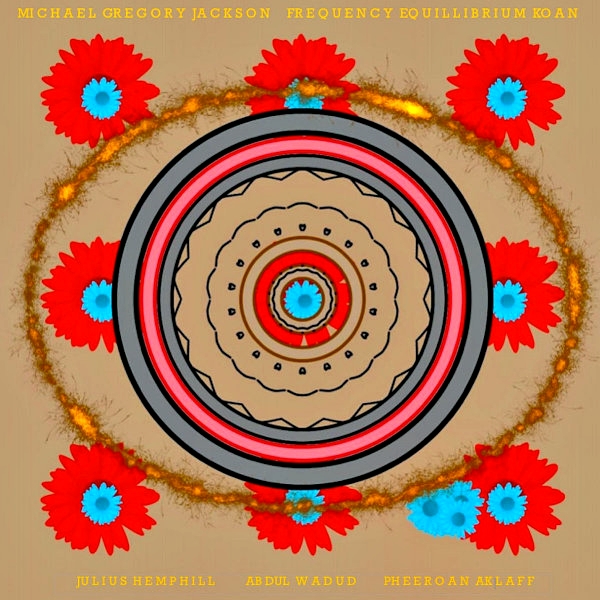

1977 – Heart & Center, from Frequency Equilibrium Koan, by Michael Gregory Jackson (quartet w. Jackson-Hemphill-Abdul Wadud-Pheeroan AkLaff) (Bandcamp)

Only released in 2021, this is a splendid archival find, featuring the compositions of a then 23-year-old Jackson, played by a stellar quartet.

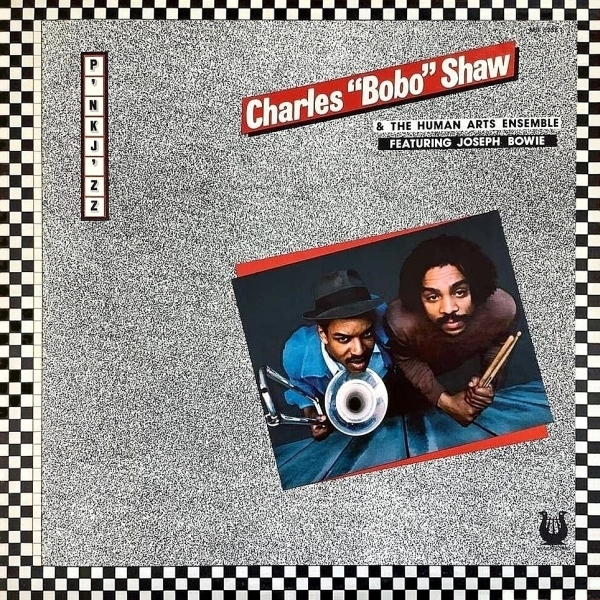

1978 – Jaki Bee Tee, from P’nk J’zz (a.k.a. Concere Ntasiah) by Charles ‘Bobo’ Shaw and the Human Arts Ensemble (sextet w. Shaw-Hemphill-Joseph Bowie-Abdul Wadud-Francois Nyomo Mantuila-Alex Blake) (Universal Justice/Muse) (YouTube – go to 9:55)

A somewhat less ragged version of Shaw’s Human Arts Ensemble, with some fine contributions by Hemphill on soprano.

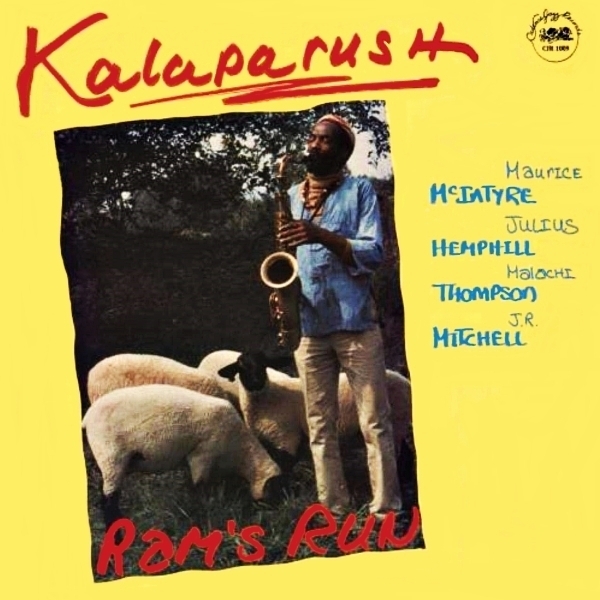

1981 – Mountain Duty, from Ram’s Run by Kalaparush Maurice McIntyre (quartet w. McIntyre-Hemphill-Malachi Thompson-J.R. Mitchell) (Cadence) (YouTube – go to 27:00)

Not my favourite context for Hemphill – his sideman dates often seem to involve some less than ideal settings – but he solos stirringly.

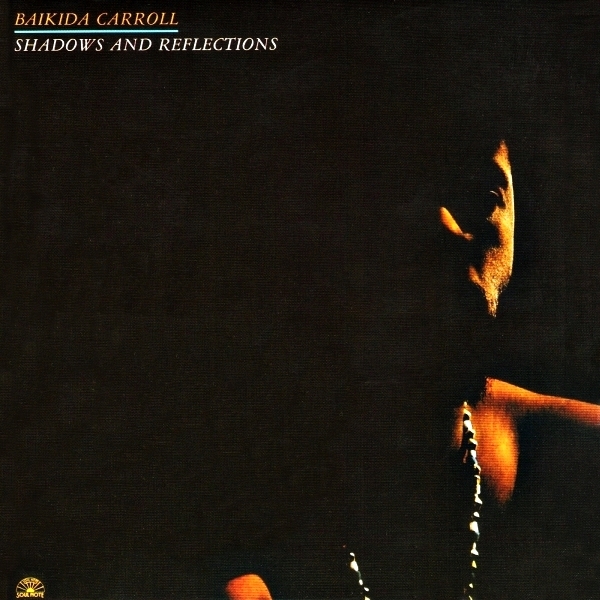

1982 – Left Jab, from Shadows and Reflections by Baikida Carroll (quintet w. Carroll-Hemphill-Anthony Davis-Dave Holland-Pheeroan AkLaff) (Soul Note) (YouTube)

A Hemphill sideman date with a group led by Carroll, one of his early collaborators – a fine post-bop recording with an excellent quintet.

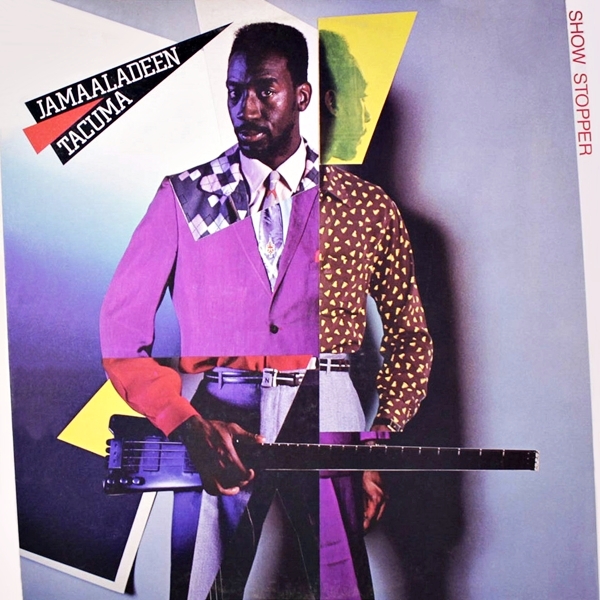

1983 – Show Stopper, from Show Stopper by Jamaaladeen Tacuma (quintet w. Tacuma-Hemphill-Olu Dara-Cornell Rochester-Barbara Walker) (Gramavision) (Bandcamp)

Hemphill appears only on this track, filling the Ornette role in Tacuma’s Prime Time-inspired band, but remaining quintessentially Hemphill.

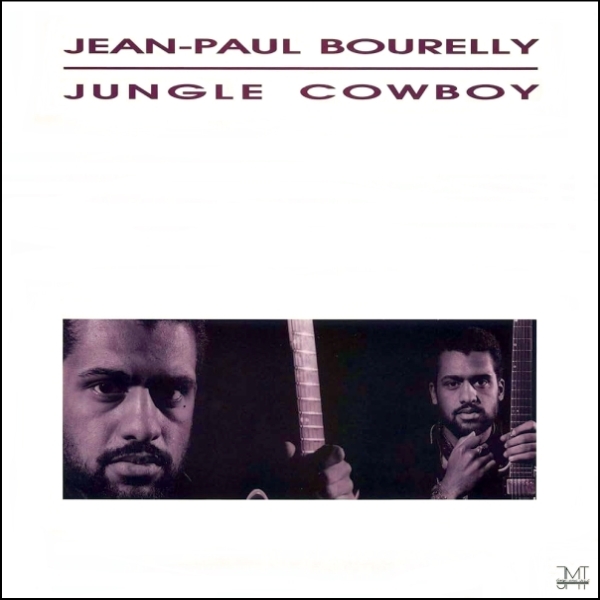

1986 – Drifter, from Jungle Cowboy, by Jean-Paul Bourelly (w. Bourelly-Hemphill-Freddie Cash-Kevin Johnson-Kelvyn Bell-Carl Bourelly-Greg Carmouché) (JMT/Winter & Winter) (YouTube) (The Winter & Winter reissue has a revised cover).

Julius gets down and dirty with electric guitarist Jean-Paul on several tracks.

1986 – One man’s hatred cannot alter another man’s destiny, from Music for Yoruba Proverbs by Bill Cole & Untempered Ensemble (octet w. Cole-Hemphill-Olu Dara-Abdul Wadud-Joseph Daley-Gerald Veasley-Warren Smith-Hafiz Shabazz) (Bandcamp)

All compositions by Cole, with arrangements by Hemphill, recorded live at Symphony Space in New York City.

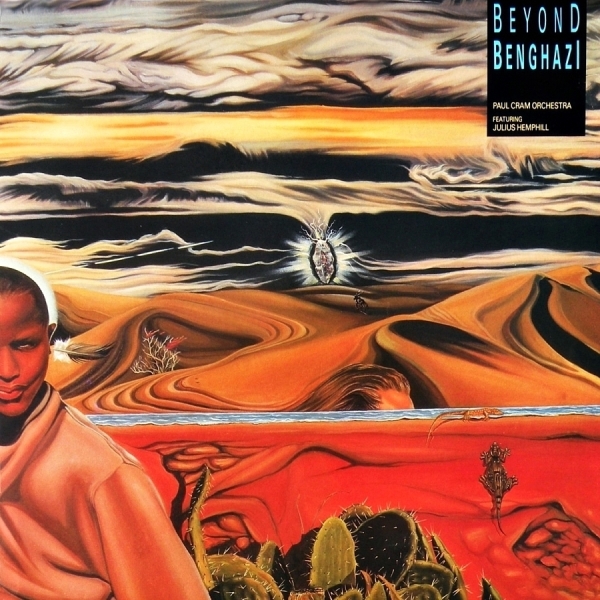

1987 – Zones; The Problem; Beyond Benghazi from Beyond Benghazi by the Paul Cram Orchestra (tentet w. Cram-Hemphill-Nic Gotham-Richard Underhill-Michael White-Tom Walsh-John Gzowski-Taras Chornowol-James Young-Richard Wynston) (Apparition/Condition West Recordings) (Also available on Bandcamp)

A splendid piece of Canadian Content, recorded in Hamilton, Ontario with an outstanding band and Paul’s fascinating charts. Notwithstanding the one-off nature of the meeting, Hemphill meshes beautifully with the ensemble, contributing powerful solos on his three featured tracks. Trombonist Tom Walsh tells an intriguing story from this session regarding Hemphill’s prodigious musical talents: having arrived late from the airport, Julius joined the band at the end of lunch and memorized the previously unseen charts in five minutes!

1988 – Some Song and Dance: Love Motel; Pip, Squeak, from Before We Were Born by Bill Frisell (septet w. Frisell-Hemphill-Billy Drewes-Doug Wieselman-Hank Roberts-Kermit Driscoll-Joey Baron) (Elektra/Musician)

Having been a member of Hemphill’s JAH Band in the mid-1980s (a version of the group that, sadly, remained unrecorded), Frisell returned the favour by inviting the saxophonist to perform as a guest soloist in his Some Song and Dance suite. Highlighting some of his foundational influences, Julius solos magnificently on the slow blues, Love Motel, and also contributes in animated fashion to the perky number, Pip, Squeak.

1988 – Rock Suite: Spuds, from A Lot of Lovin’ by Killing Floor (trio w. Larry Simon-Brian Jost-Andrew James Johnson + Hemphill) (OSA Records)

This is one of the more obscure and hard-to-find records in Hemphill’s discography, self-released by the band after being told they were “too mainstream” by Michael Dorf at the Knitting Factory. Hemphill plays with fire and passion on this one track, which bandleader and guitarist Larry Simon has been kind enough to post on his website.

1989 – Monk, from Dreamland by Darrell Katz and the Jazz Composers Alliance Orchestra (28-piece orchestra w. Katz-Hemphill-Rob Scheps-Russ Gershon-Charlie Kohlhase-Dave Balou-Curtis Hasselbring-Josh Roseman-John Medeski-George Schuller-et al.) (Cadence) (Apple Music)

Hemphill is a soloist on this Katz composition, with a big band comprising the JCAO and members of the Either Orchestra and Orange Then Blue.

1990 – The Gift, from At the Moment of Impact… by Allen Lowe (quartet w. Lowe-Hemphill-Jeff Fuller-Ray Kaczynski) (Fairhaven) (Bandcamp)

Having initially approached Tim Berne, who turned down the gig, tenor saxophonist and composer Lowe invited Hemphill to participate in several interesting but somewhat restrained quartet sessions, with Julius also featured on Krapp’s Last Breath, Argentinian Slow Drag, Long Dreams, and Blues for Eddie Durham and Dicky Wells, all available on Lowe’s Bandcamp site.

1990 – Balances & Cloves, from Duos: America by Peter Kowald (FMP) (Bandcamp)

Hemphill appears only on this track, as one of many partners in Kowald’s amazing Duos project. See/hear also Live at Kassiopeia (1987).

1991 – March of the Vipers, from New Tango ’92 – After Astor Piazzolla (or, The Second Assassin) by Allen Lowe and Orchestra X (septet w. Lowe-Hemphill-Paul Austerlitz-Robert Rumbolz-John Rapson-Jeff Fuller-Ray Kaczynski) (Fairhaven) (Bandcamp)

It’s not every day that you see the credit “Featuring Doc Cheatham and Julius Hemphill” on the back cover of a CD, but, regrettably, they don’t play in the same group, with the veteran trumpeter appearing only on two quartet tracks with Lowe. The rest of the album features a powerful septet recorded live at the Knitting Factory in New York City, with Hemphill prominently featured on several tracks, although I must confess that the Piazzolla connection remains a little obscure to my ears.

1992 – The Hard Blues, from Flux by the Jazz Composers Alliance Orchestra with Julius Hemphill and Sam Rivers (Northeastern) (Apple Music)

Hemphill solos intensely on his own composition The Hard Blues, on what would be his last guest appearance on record.

4) Recordings of Hemphill’s Compositions by Other People

1975 – Lonely Blacks, on Heavy Spirits by Oliver Lake (solo alto saxophone) (Arista-Freedom) (Source: No previous recording)

1989 – Parchment, from American Piano Music of Our Time (Ursula Oppens – piano) (Music & Arts) (Source: No previous recording)

A rare Hemphill composition for piano, an instrument that appears nowhere else in his discography (other than on a couple of sideman sessions). A 2007 performance of Parchment, also by Oppens, is available on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony. And see/hear also One Atmosphere, for piano and string quartet, on the Tzadik album of the same name.

1990 – The Hard Blues, from The Calculus of Pleasure by Either/Orchestra (tentet w. Russ Gershon-Charlie Kohlhase-Curtis Hasselbring-John Medeski-Matt Wilson-et al.) (Accurate) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

1991 – The Painter, from Emergency Peace by Marty Ehrlich’s Dark Woods Ensemble (trio w. Ehrlich-Abdul Wadud-Lindsey Horner) (New World) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

1992 – C, from Sankofa/Rear Garde by Hamiet Bluiett (quartet w. Bluiett-Ted Dunbar-Clint Houston-Ben Riley) (Soul Note) (Source: Raw Materials and Residuals)

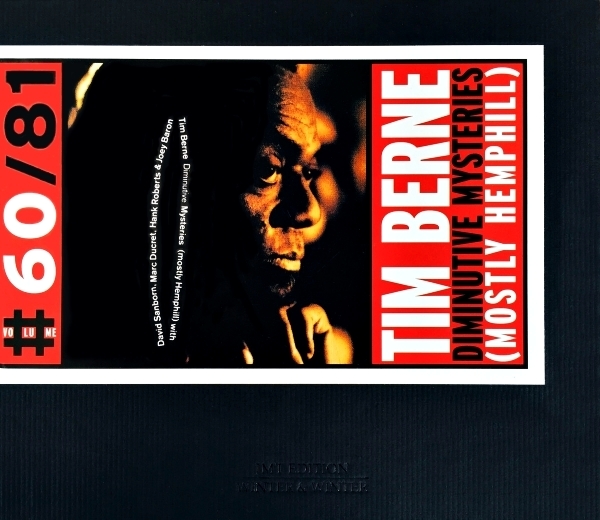

1992 – Sounds in the Fog, from Diminutive Mysteries (Mostly Hemphill) by Tim Berne (quintet w. Berne-David Sanborn-Marc Ducret-Hank Roberts-Joey Baron) (JMT/Winter & Winter) (The Winter & Winter reissue has a revised cover) (Bandcamp) (Source: No previous recording)

A former student and associate of Hemphill’s, Berne has been one of his great supporters, recording numerous Hemphill compositions, reissuing Blue Boyé in 1998 on his own Screwgun label, and producing this fascinating album, which features five new pieces by Hemphill, written especially for this project. The album also includes two existing Hemphill compositions, Rites (from Dogon A.D.) and Mystery To Me (written for Fontella Bass as part of a staged presentation in St Louis in 1976, entitled Coontown Bicentennial Memorial Service), plus an original composition by Berne, The Maze (for Julius). In his liner notes, praising Berne for “creating and pursuing” the project, Hemphill states: “This meeting of the minds has been one of the most rewarding experiences I have had.” And David Sanborn has never sounded hipper.

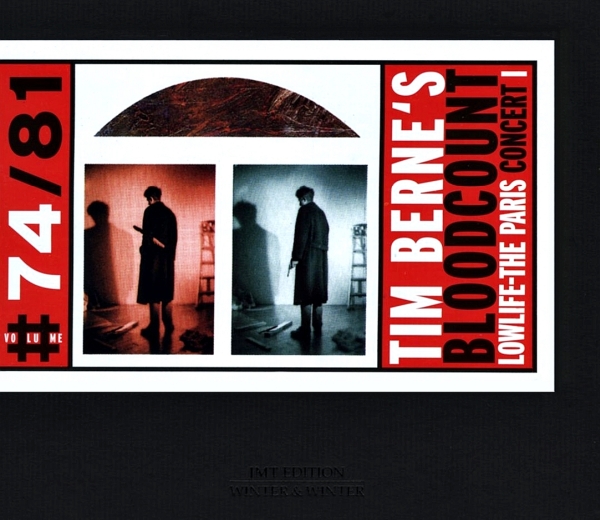

1994 – Reflections/Lyric/Skin 1, from Lowlife: The Paris Concert 1 by Tim Berne’s Bloodcount (quintet w. Berne-Chris Speed-Marc Ducret-Michael Formanek-Jim Black) (JMT/ Winter & Winter) (The Winter & Winter reissue has a revised cover) (Bandcamp) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

1995 – Georgia Blue, from New York Child by Marty Ehrlich (quintet w. Ehrlich-Stan Strickland-Michael Cain-Michael Formanek-Bill Stewart) (Enja) (Source: Georgia Blue)

1996 – The Painter, from Live Wood by Marty Ehrlich’s Dark Woods Ensemble (trio w. Erik Friedlander-Mark Helias) (Music & Arts) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

1997 – The Hard Blues, from Talkin’ Stick by Oliver Lake (quintet w. Lake-Geri Allen-Jay Hoggard-Belden Bullock-Cecil Brooks III) (Passin’ Thru) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

1997 – R & B, from I’m Me And You’re Not: The Music of Darrell Katz by the Jazz Composers Alliance Saxophone Quartet (Jeff Hudgins-Eric Rasmussen-Phil Scarff-Dan Bosshardt) (Brownstone) (Not available online) (Source: World Saxophone Quartet – Steppin’ with the World Saxophone Quartet)

1998 – Mirrors, from Dancing On My Bedpost by Charlie Kohlhase Quintet (w. Kohlhase-Matt Langley-John Carlson-John Turner-Matt Wilson) (CIMP) (Not available online) (Source: Raw Materials and Residuals)

1998 – Four Saints, from Gigtime 2000: Vol. 4 “Keep On Dancin’, Baby!” by Andrew White (quartet w. White-Allyn Johnson-Steve Novosel-Howard Curtis) (Andrew’s Music) (Not available online) (Source: Fat Man and the Hard Blues)

1999 – Pigskin, from Malinke’s Dance by Marty Ehrlich’s Traveler’s Tales (quartet w. Ehrlich-Tony Malaby-Jerome Harris-Bobby Previte) (OmniTone) (Not available online) (Source: Julius Hemphill Big Band)

Ehrlich notes that Pigskin had been previously recorded as the fourth movement of Drunk on God, from Julius Hemphill Big Band, featuring poet K. Curtis Lyle, where it was retitled as ‘Motion as the Terrible Language of the Future’. A quartet version of Pigskin (1982), featuring Hemphill on alto, Jack Wilkins on guitar, Jerome Harris on electric bass, and Michael Carvin on drums, was later released on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony.

1999 – Skin 1, from Skin by Erik Friedlander (quartet w. Friedlander-Andy Laster-Stomu Takeishi-Satoshi Takeishi) (Siam) (Not available online) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

2001 – C.M.E./G Song, from Free Jazz Classics Vols. 1 & 2 by The Vandermark 5 (w. Ken Vandermark-Dave Rempis-Jeb Bishop-Kent Kessler-Tim Mulvenna) (Atavistic) (Sources: Blue Boyé/Raw Materials and Residuals)

2002 – Pensive, from Live! by CK5 (quintet w. Charlie Kohlhase-Jason Hunter-Matt Langley-Eric Hofbauer-Scott Barnum) (Creative Nation) (Not available online) (Sources: Live in New York/Wildflowers 4: The New York Loft Jazz Sessions)

2008 – C (interpolated, at 6:34, into the closing piece on the album, Sold at a Ten Percent Discount), from The Disappointment of Parsley by The Rempis Percussion Quartet (w. Dave Rempis-Anton Hatwich-Tim Daisy-Frank Rosaly) (Not Two Records) (Not available online) (Source: Raw Materials and Residuals)

2008 – Anchorman, from Present Tense by James Carter (quintet w. Carter-Dwight Adams-D. D. Jackson-James Genus-Victor Lewis) (EmArcy) (Sources: Julius Hemphill Big Band/Fat Man and The Hard Blues) (Note: Anchorman is included as a bonus track only on the Japanese edition of the Carter CD, which is not available online.)

2008 – Dung; Slices of Light; Dogon A.D., from Things Have Got To Change by Marty Ehrlich’s Rites Quartet (w. Ehrlich-James Zollar-Erik Friedlander-Pheeroan AkLaff) (Clean Feed) (Sources: No previous recording; No previous recording; Dogon A.D.)

In addition to his archival work, Ehrlich has championed the recording of Hemphill’s compositions, several of which have been included on his own records. Alongside the warhorse Dogon A.D., this album features two previously unheard pieces, offering an intriguing glimpse into the still untapped depths of Hemphill’s catalog, which Ehrlich estimates at approximately 250 compositions. A version of Dung (1979) is also available on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony, performed by an amazing, one-off quartet of Hemphill, Baikida Carroll, Dave Holland, and Jack DeJohnette.

2008 – Dogon A.D., from Pasborg’s Odessa 5 by Stefan Pasborg (quintet w. Pasborg-Anders Banke-Jonas Müller-Mads Hyhne-Jakob Munck) (Stunt Records) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

2008 – Dogon A.D., from L.O.V.E. by Pospaghemme (duo w. Beppe Scardino-Federico Scettri) (El Gallo Rojo) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

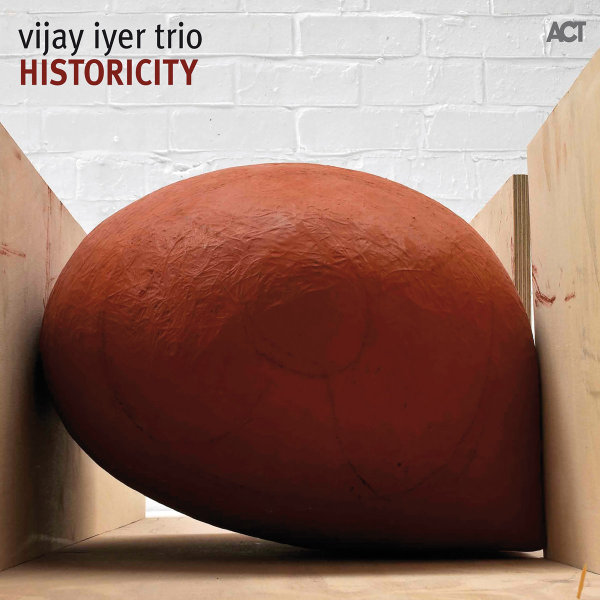

2009 – Dogon A.D., from Historicity by Vijay Iyer (trio w. Iyer-Stephan Crump-Marcus Gilmore) (ACT) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

2009 – Kansas City Line, from The Edenfred Files by Darryl Harper (quartet w. Harper-Kevin Harris-Matthew Parrish-Harry ‘Butch’ Reed) (HIPNOTIC) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: Blue Boyé)

2011 – The Hard Blues, from At the Crossroads by James Carter’s Organ Trio (w. Carter-Gerard Gibbs-Leonard King, Jr. plus Brandon Ross) (EmArcy) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

2011 – The Painter, from Like a Tree by Kirk Knuffke/Jesse Stacken/Kenny Wollesen (trio) (SteepleChase) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

2014 – C; The Hard Blues/Skin 1, from The Midwest School by Audio One (tentet w. Ken Vandermark-Dave Rempis-Mars Williams-Nick Mazzarella-Josh Berman-Jeb Bishop-Jen Paulson-Jason Adasiewicz-Nick Macri-Tim Daisy) (Audiographic) (Bandcamp) (Sources: Raw Materials and Residuals; ‘Coon Bid’ness)

2014 – The Hard Blues, from Hoodoo Blues by Roots Magic (quintet w. Alberto Popolla-Errico De Fabritiis-Gianfranco Tedeschi-Fabrizio Spera-Luca Venitucci) (Clean Feed) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

2014 – Floppy; Dogon A.D.; Body; Hotend; The Hard Blues; G Song, from Hotend: Do Tell Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill by Do Tell (trio w. Dan Clucas-Mark Weaver-Dave Wayne) (Amirani) (Sources: Fat Man and the Hard Blues/Live from the New Music Cafe; Dogon A.D.; Flat-Out Jump Suite; Blue Boyé; ‘Coon Bid’ness; Raw Materials and Residuals)

The only album out there dedicated entirely to Hemphill compositions (although Tim Berne’s Diminutive Mysteries (Mostly Hemphill) comes close), played by Do Tell, a fascinating trio of cornet, tuba, and drums/electronics, which, despite the apparent limitations of the instrumentation, succeeds in capturing the spirit of Hemphill’s music in ways both playful and profound.

2016 – Dogon A.D., from Last Kind Words by Roots Magic (quintet w. Alberto Popolla-Errico De Fabritiis-Gianfranco Tedeschi-Fabrizio Spera-Luca Tilli) (Clean Feed) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

2018 – Dogon A.D., from Dogon Revisited by Salim Washington (quartet w. Melanie Dyer-Hilliard Greene-Tyshawn Sorey) (Passin’ Thru) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

2018 – Body; Dogon A.D., from Broken Shadows by Broken Shadows (quartet w. Tim Berne-Chris Speed-Reid Anderson-Dave King) (Intakt) (Sources: Flat-Out Jump Suite; Dogon A.D.)

2018 – Reflections, from Diatom Ribbons by Kris Davis (tentet w. Davis-Esperanza Spalding-J.D. Allen-Tony Malaby-Ches Smith-Nels Cline-Marc Ribot-Trevor Dunn-Val Jeanty-Terri Lyne Carrington) (Pyroclastic) (Source: ‘Coon Bid’ness)

2019 – Body; Dogon A.D., from Broken Shadows Live by Broken Shadows (quartet w. Tim Berne-Chris Speed-Reid Anderson-Dave King) (Screwgun) (Bandcamp) (Sources: Flat-Out Jump Suite; Dogon A.D.)

2019 – Dear Friend, from The Fantastic Mrs. 10 by Tim Berne’s Snakeoil (quintet w. Berne-Oscar Noriega-Marc Ducret-Matt Mitchell-Ches Smith) (Intakt) (Source: No previous recording)

Rescued from the archive by Berne and given a sublimely beautiful reading by the members of Snakeoil, this was a previously unheard Hemphill composition which later appeared on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony in a quartet recording from 1980 in Florence, featuring Hemphill on alto and tenor, Olu Dara on trumpet, Abdul Wadud on cello, and Warren Smith on percussion.

2019 – Dogon A.D., from Dancing In Your Head(s) by Orchestre National de Jazz (15-piece orchestra directed by Frédéric Maurin plus Tim Berne) (ONJ) (Also available on Bandcamp) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

Just when you thought you didn’t need yet another cover of Dogon A.D., along comes the ONJ, plus fiery guest soloist Berne, with a riotous guitar-led big band version that also features great work from Susana Santos Silva on trumpet and Bruno Ruder on Fender Rhodes. Splendid stuff.

2020 – Rites, from Light Line by Chris Speed (solo clarinet) (Intakt) (Source: Dogon A.D.)

2021 – Number 2, from One More, Please by Tim Berne/Matt Mitchell (duo) (Intakt) (Source: The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony)

Berne continues mining the Hemphill archive in his duo with pianist Mitchell, offering a reading of a piece first heard on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony in a trio version recorded in Berkeley, California in 1977 with Hemphill, Baikida Carroll, and Alex Cline.

Julius Hemphill and Björk: The Story of a Non-Relationship

There has been considerable confusion regarding Hemphill’s supposed involvement in Björk’s album Debut Live (1994), given that Hemphill’s name (with his last name misspelled) appears in the booklet notes for the CD. The recordings for Debut Live were made for the MTV Unplugged television series in New York City on November 7, 1994, and include two gorgeous pieces, Aeroplane and Anchor Song, which feature a saxophone trio comprised of Oliver Lake on soprano, Dan Lipman on tenor, and Ike Leo on baritone, who can be seen performing on the DVD of the concert. Aeroplane and Anchor Song were first recorded for Debut (1993), by a trio featuring Lake, Gary Barnacle, and Mike Mower, with arrangements by Lake, who is appropriately credited in the CD booklet. These are the same arrangements that were used for the Debut Live concert recording. Hemphill’s name does not appear on the DVD credits, and Oliver Lake has confirmed in email correspondence with me that Hemphill, who, as noted above, had been forced to stop playing the saxophone following heart surgery in 1993, had no involvement in the Debut Live recording sessions. Hemphill’s listing in the CD booklet for Debut Live therefore remains something of a mystery (and if anyone can shed light on this issue I would be grateful for any information). Unfortunately, this erroneous credit has generated multiple inaccurate online references to Hemphill’s purported involvement in Debut Live, which the evidence on the MTV Unplugged DVD simply denies. Having said all of that, Barry Marsden’s picture of Björk in Ray’s Jazz Shop in London in 1994 with a copy of Buster Bee tucked under her arm is kinda cool.

Julius Hemphill and Joseph Bowie: The Story of an Unrelated Song Title

The composition Dogon A.D. by the trombonist Joseph Bowie, which first appeared on the Defunkt album Cum Funky in 1993, is, indeed, a funky, fast-paced thang that has no relation to Hemphill’s composition of the same name (and it receives appropriate composer and publishing credits on the live album Classic Defunkt). By the 1990s, Hemphill’s Dogon A.D. was already firmly established as one of his signature pieces, and why Joseph, brother of Lester, and an occasional Hemphill collaborator, would have chosen this name for a composition of his own is another currently unresolved mystery. Answers on a postcard, please.

A chronological cover art gallery of Hemphill’s own recordings, guest/sideman appearances, and recorded performances of his compositions

© Alan Stanbridge 2024